Stop the Presses

October 28, 2025

This article originally appeared in the November 1995 issue of the magazine, then called Demolition Age.

The recently published Demolition Insert, which appeared in McGraw-Hill’s Engineering News Record on Sept. 18 touted the detective skills and scientific acumen of the nation’s demolition contractors. The engineering skills and construction savvy that the demolition industry brings to its work are legendary throughout the construction industry.

There is also an art to the work the industry performs. This artwork can prove financially rewarding, and it can also be a lot of fun.

Former NDA President Harold Hudgins’ job atop Stone Mountain in Atlanta, featured in the ENR insert, is the “most fun he has had in years.”

Carl Mason, president of Narberth, Pennsylvania-based Central Salvage, used those exact same words to describe the job his firm is doing for PNI, Philadelphia Newspapers Inc., publishers of Philadelphia’s two daily newspapers, The Philadelphia Inquirer and the Philadelphia Daily News. Like so many demolition contractors, Mason said removal of the printing facilities in the PNI’s center city Philadelphia plant was “a job I wanted.”

“I grew up in the city and have driven past the historic Inquirer building a thousand times on my way into the city. I knew I had to do this job,” Mason said.

“Since we began the project in August, I’ve talked to any number of people in the city who worked for The Inquirer or worked on its presses. They were all as excited as I was about the project. We are dismantling a part of the city’s history.”

The Work

The Inquirer project involves the removal of all the printing capabilities of PNI at its Philadelphia headquarters. Central, working with Turner Construction Co., is removing 102 presses that used to print the region’s two daily newspapers.

The Inquirer project involves the removal of all the printing capabilities of PNI at its Philadelphia headquarters. Central, working with Turner Construction Co., is removing 102 presses that used to print the region’s two daily newspapers.

The work area included the plant’s basement area where the newsprint would arrive on rail cars, a giant mailroom where the papers were loaded for distribution, the reel room where the newsprint was loaded into the presses and the massive press room where the newspapers were printed. These processes were housed in two separate structures joined by an infill building.

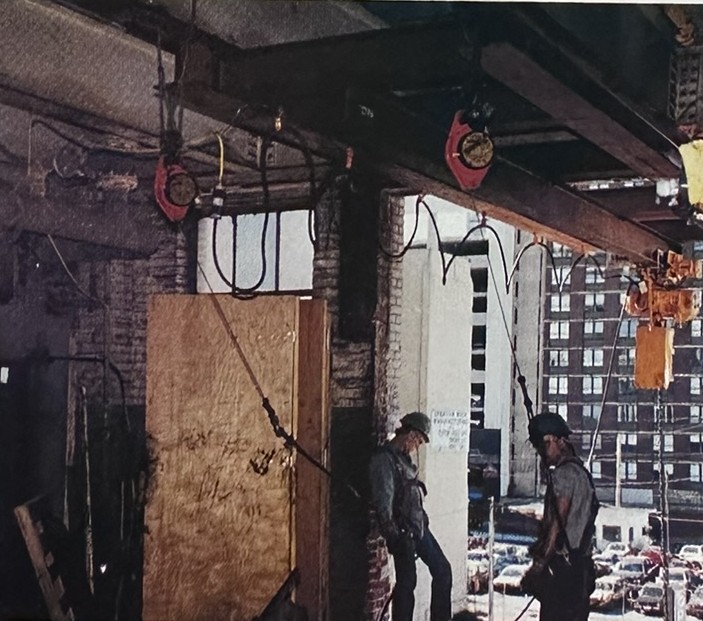

It is a massive undertaking fraught with challenges. First, the magnitude of the building itself. Occupying an area covering four city blocks, the structure above the press floors remained in use during the demolition.

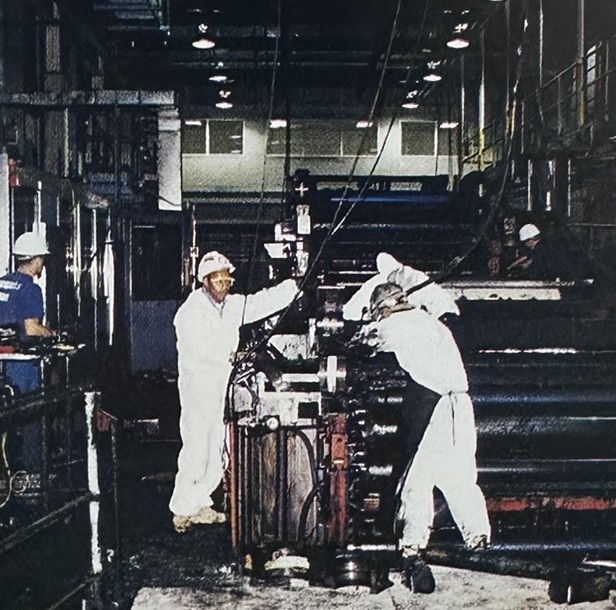

Consequently, Central had to minimize the noise and dust generated during the work. More importantly, the client prohibited the use of torches in the press room. No burning.

This meant that 102 newspaper presses, each weighing between 55,000 and 60,000 pounds, had to be “disassembled” in a little over four months.

This disassembly brought about some interesting labor problems for Central. While demolition of this type is certainly the purview of the Laborers International, the mechanics that maintained the presses from the Aerospace and Machinist Workers Union also claimed the work. But more on that later.

In order to print two daily newspapers are a center city location, PNI’s headquarters evolved into a compact operation running over four floors. This, and the ink used to print the papers, produced a stygian labyrinth of presses, conveyors, ductwork, electrical lines and other utilities that Central Salvage first had to figure out in order to remove.

Initially, Central began loading the disassembled presses out of a second-story opening in the building’s south side. Mason, Central’s project manager Bob Verzella and superintendent Art Nelson realized pretty quickly that this procedure was just too slow. After careful evaluation of the flow of the work, they opted to lower the presses through the building using a series of lifts by forklifts on special loadout days. Their productivity increased dramatically. One problem down.

Press Disassembly

In order to price the job, Central decided to take the unprecedented step of offering to disassemble one of the presses, at their own cost, to see how long it would take. Early in August, a five-man crew from Central worked 24 hours straight to determine the best method to disassemble a press.

In order to price the job, Central decided to take the unprecedented step of offering to disassemble one of the presses, at their own cost, to see how long it would take. Early in August, a five-man crew from Central worked 24 hours straight to determine the best method to disassemble a press.

Mason used the information developed during this test run to determine his job costs for the project and to iron out some of the problems he foresaw during the bid walk. A press disassembly procedure was born.

Mason believes the entire project will produce over 5,000 tons of scrap, 3,000 tons in the 102 presses alone and another 2,000 tons in the ductwork, conveyors, steel flooring, catwalks, utilities and other miscellaneous metals. The project contains plate and structural, copper in the insulated wiring, light iron and castings in many of the systems and the heavy iron of the rollers in the press.

Labor

One of the more unusual elements of this project has been the cooperation between the various players. Central has worked hard with the owner and its unions, the construction manager and with their own trades to develop a program to make the best use of all the people involved with the project.

Mason arranged for a series of meetings with local union officials to hammer out a landmark agreement that would keep everyone happy. Working closely with the trade organizations that Central was signatory with, Mason was able to hire a number of machinists who had been maintaining the presses for years. These machinists brought invaluable expertise to the disassembly process.

Central’s total labor force included some 20 machinists, 35 to 40 laborers and four operating engineers.

Safety & Environmental Issues

The removal of 102 newspaper presses presented Central with some tough environmental and safety issues.

The removal of 102 newspaper presses presented Central with some tough environmental and safety issues.

Their first concern was the ink.

Printing two daily newspapers obviously requires a lot of ink. It is everywhere on the press floors. Every nook and cranny of the presses was coated with it, sometimes as a thin gloss, in other places a congealed goo.

The client was very concerned about the handling and disposal of this nonhazardous substance. They wanted to make sure Central did not trail any ink through the streets of Philadelphia on their way to the scrap yard.

Therefore, PNI designated a pre-approved scrapyard for the recycling of the presses. The client evaluated a number of area yards and selected a firm they felt had an environmental program, including a run-off retention system, that would assure safe handling of the ink-laden presses.

Although the ink is nonhazardous, it is pervasive. Mason believes that one of the largest single expenditures on the job will be the Tyvek disposable suits for his workforce. Central also adjusted their work schedule to allow for extra cleanup time for their workers before lunch.

The windowless environment of the four floor press area, with its black ink everywhere, presented Central with some interesting safety challenges.

As six separate press lines, A through F, run between floors, Central had to address fall protection for their workers right away. Rather than attempt to tether their highly mobile workers to a cumbersome overhead system, Central’s project executive Bob Verzella designed a system of safety rails around all the open floor areas. This system, installed and paid for by Central, assured the safety of the workers while allowing for access to the presses.

During the first loadout phase of the project on the plant’s south side, Central installed special retractable lanyards and harnesses to guarantee the safety of their loadout workers.

One of the client’s major concerns during those phases of the work when torch cutting was required was lead.

Mason believes that one of the reasons PNI selected Central for this work was the NDA’s Lead-in-Construction training program. Central had a fully implemented lead program in place, including blood monitoring, worker training and air monitoring. While the bulk samples collected during the startup phase of the work revealed minimal lead in the pain in the building, in those locations where lead was present, Central maintained a complete lead control program. Analysis of the air samples taken during those operations revealed numbers well below the OSHA standard.

The project also contained some asbestos and PCBs. The asbestos that did exist on the press floors had been abated prior to Central starting their work. The PCBs in the transformers on the floors was handled according to EPA guidelines.

Controlling the Job

The secrets to successfully completing a project as elaborate as this one are coordination and cooperation.

Mason believes that the PNI project is progressing so smoothly because of the cooperation he has received from all the players involved.

He has worked closely with the client on all phases of the project from safety and environmental issues through labor negotiations and project planning. PNI’s labor negotiations helped arrange the compromise with their machinist’s union.

Mason developed a good relationship with PNI’s construction manager, Turner Construction Co., which helped with the pre-project planning and coordination.

Much of Central’s success at PNI Mason credits to his longtime superintendent Art Nelson. Nelson has been able to coordinate the efforts of over 70 workers disassembling 102 presses and their assorted utilities over four floors. He basically has been running six separate jobs, all loading scrap out of one central location. He has juggled his workforce through a series of different press lines and orchestrated Central’s five forklifts, six different hoists, three articulated booms and three skid steers roaming throughout the building.

Nelson has dealt with three separate trades, a myriad of logistical problems and the expanse of a project spanning over four floors four city blocks long. Mason states that Nelson has done “his usual masterful job keeping all this together.”

Mason believes the success of his firm has been the cooperative spirit of all his people. He believes strongly in the importance of teamwork and keeping the needs of the client in mind at all times. He and his wife, Bobbi, who is vice president/chief financial officer of Central and the company’s chief troubleshooters, stress the importance of teamwork on all their jobs.

He believes his company, started in 1981, has grown into one of the largest interior demolition firms in the region because he has succeeded in convincing his workforce of the importance of teamwork and customer satisfaction.

Mason says, “We work as a team all the time and keep the needs of customers foremost in our minds. That’s been the key to our success. By the way, it is possible to occasionally have fun, too.”